Table of Contents

- Introduction: The ESG Imperative in Modern Business

- What is ESG Risk Management? Moving Beyond Compliance

- The Three Pillars of ESG: A Comprehensive Framework

- Systematic vs. Unsystematic ESG Risks: A Core Distinction

- How to Implement an ESG Risk Management Framework

- An Overview of Key ESG Reporting Frameworks

- Conclusion: Turning ESG Risk into a Strategic Advantage

- Introduction: The ESG Imperative in Modern Business

Introduction: The ESG Imperative in Modern Business

The contemporary business landscape is undergoing a fundamental shift. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors are no longer peripheral concerns but central drivers of corporate risk and strategic opportunity. This is not a passing trend but a structural change in how organizations create and sustain long-term value.

Recent data underscores the magnitude of this transformation. The 2023 EY Global C-suite Insights Survey reveals that over 81% of organizations have established Chief Sustainability Officer (CSO) positions or equivalent leadership roles, with 90% of executives reporting board-level oversight of ESG agendas (Watson et al., 2023).

This article is the second installment in our AI-Driven Risk Management series, building on our foundational post on understanding systematic risk. We apply the core principle, that total risk is the sum of systematic and unsystematic risks, specifically to the ESG domain. We demonstrate how market-wide (systematic) and company-specific (unsystematic) ESG factors combine to form an organization’s comprehensive ESG risk profile.

What is ESG Risk Management? Moving Beyond Compliance

ESG provides a tangible framework for evaluating an organization’s impact across three critical dimensions. Unlike broader concepts like Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), ESG offers measurable criteria that enable data-driven decision-making for companies and investors alike.

The strategic imperative for ESG management stems from several interconnected forces: powerful market pressures, evolving regulations, and shifting stakeholder expectations. Investors are systematically integrating ESG factors into asset management, while regulators like the EU are implementing stringent requirements such as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). Failure to adapt exposes organizations to significant financial, regulatory, and reputational damage.

Ultimately, proactive ESG management is directly linked to financial performance.

A 2023 study by the IBM Institute for Business Value found that organizations recognized as ESG leaders are 43% more likely to outperform peers in profitability.

– (Krantz & Jonker, 2023)

This evidence reframes ESG not as a cost center, but as a critical driver of competitive advantage and long-term resilience.

The Three Pillars of ESG: A Comprehensive Framework

Effective ESG management requires a holistic assessment of three interconnected pillars:

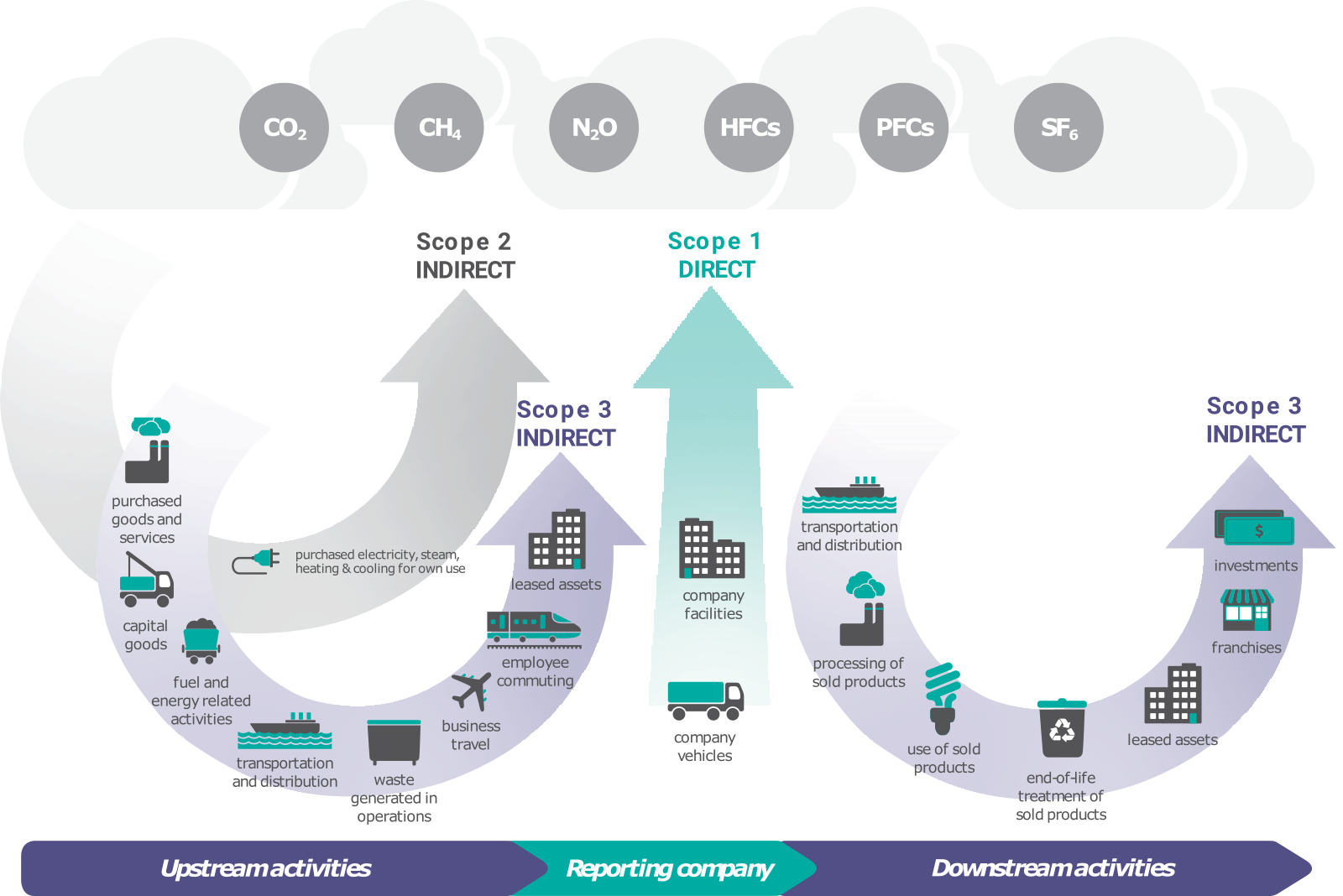

- Environmental: This pillar examines an organization’s impact on the natural world. It covers climate change mitigation, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions management, resource depletion, waste, and pollution. Key risk categories include Transition Risks (e.g., from carbon pricing) and Physical Risks (e.g., from extreme weather events).

- Social: The social dimension addresses a company’s relationship with its employees, customers, and the communities in which it operates. Key areas include diversity and inclusion, human rights, labor standards, data privacy, and supply chain ethics. Strong social performance enhances brand reputation and talent retention.

- Governance: This focuses on a company’s leadership, internal controls, and shareholder rights. Critical elements include board composition, executive compensation, transparency in reporting, and ethical business conduct. Robust governance reduces operational risks and builds stakeholder confidence.

Systematic vs. Unsystematic ESG Risks: A Core Distinction

As established in the first article of our series, an organization’s total risk can be decomposed into two parts. This principle is directly applicable to ESG risk:

Total ESG Risk = Systematic ESG Risk + Unsystematic ESG Risk

- Systematic ESG Risk: These are market-wide ESG factors affecting all organizations within a sector or economy. Examples include sweeping climate regulations, major shifts in societal attitudes toward sustainability, or global supply chain disruptions from environmental events. These risks cannot be diversified away and require systemic, industry-level responses.

- Unsystematic ESG Risk: These are company-specific ESG factors unique to an individual organization. Examples include a governance scandal, a localized environmental incident, a labor dispute, or an ethical violation in the company’s supply chain. These risks can often be mitigated through effective internal controls and strategic management.

Understanding this decomposition allows organizations to develop targeted strategies that address both broad industry challenges and unique internal vulnerabilities.

| Category | Systematic Risks | Unsystematic Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Impact | Affects a wide range of securities across the whole market or a market segment | Limited to a particular industry, company, or market segment |

| Nature | Cannot be controlled, minimized, or avoided by management | Can be managed, minimized, or completely avoided by management |

| Factors | Driven by external or macroeconomic events (e.g., geopolitical, economic, social) | Stemming from internal or microeconomic conditions |

| Protection | Managed through strategic asset allocation | Managed through portfolio diversification |

| Avoidability | Unavoidable | Avoidable and resolvable |

| Types | Includes purchasing power risk, interest rate risk, and market risk | Includes business-specific and financial risk |

Figure 1: Systematic vs. Unsystematic Components of Total ESG Risk

How to Implement an ESG Risk Management Framework

Effective ESG risk management is a systematic process of identifying, assessing, and mitigating risks and opportunities. A successful framework is built on a deep understanding of stakeholder expectations, as they are the primary drivers of ESG priorities.

Stakeholders, from investors and regulators to customers and employees, are collectively raising the bar. Investors demand transparency and integrate ESG data into their decision-making. Regulators are creating complex compliance obligations. Customers and employees prefer to align themselves with socially and environmentally responsible brands. Supplier and Value Chain Pressures, this creates cascading effects throughout value chains, compelling businesses to adopt sustainable and ethical practices across their entire operational ecosystem. A modern ESG framework must therefore be designed to address these diverse, and sometimes competing, demands in a coherent and strategic manner.

An Overview of Key ESG Reporting Frameworks

Robust measurement and transparent reporting are the cornerstones of effective ESG management. Several key frameworks provide standardized guidelines to help organizations communicate their performance to stakeholders:

- European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS): A set of mandatory standards under the EU’s CSRD. They require disclosures based on a “double materiality” approach, addressing both the company’s impact on society and the environment, and the financial risks posed by sustainability issues.

- Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD): The global benchmark for climate-related financial risk disclosure. Its recommendations are structured around four core areas: Governance, Strategy, Risk Management, and Metrics & Targets.

- Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB): Provides industry-specific standards focused on the financially material sustainability topics most likely to impact enterprise value. This enhances the relevance and comparability of disclosures for investors.

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI): A comprehensive framework for reporting on economic, environmental, and social impacts. GRI standards emphasize stakeholder engagement and materiality to focus reporting on the most significant issues.

- Integrated Reporting Framework: An integration of thinking that connects financial and non-financial information, demonstrating how organizations create value over time through effective management of financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social, and natural capital.

Conclusion: Turning ESG Risk into a Strategic Advantage

In today’s business environment, success increasingly depends on an organization’s ability to manage ESG risks with strategic foresight. As regulatory demands intensify and stakeholder expectations rise, risk management must evolve from a reactive compliance exercise into a proactive engine for value creation.

By integrating robust frameworks with emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, machine learning, and advanced analytics, companies can dramatically enhance risk assessment, prediction, and mitigation. This fusion of technical capability and strategic vision empowers firms not only to navigate the complex ESG landscape but also to unlock innovation, build lasting resilience, and secure a competitive advantage in a rapidly changing world.

References

Krantz, T., & Jonker, A. (2023). What is environmental, social and governance (ESG)? IBM Think. Retrieved from https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/environmental-social-and-governance

Mohebbi, A. (2025). Systematisches Risiko verstehen: Eine Marktkraft, die sich nicht beeinflussen lässt. Procycons. Retrieved from https://procycons.com/de/blogs/systematisches-risiko-verstehen/

UNEP Finance Initiative. (2024). European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). Retrieved from https://www.unepfi.org/impact/interoperability/european-sustainability-reporting-standards-esrs/

Watson, R., Bergman, R., Firth, C., & Schreiber, C. (2023). The EY 2023 Global Cybersecurity Leadership Insights Study shows how leaders are bolstering defenses while creating value. EY Insights. Retrieved from https://www.ey.com/en_gl/insights/consulting/is-your-greatest-risk-the-complexity-of-your-cyber-strategy